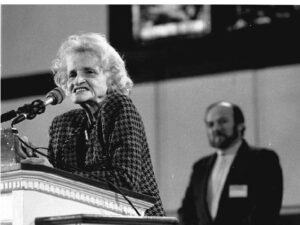

Celebrating Women's History: Sylvia Olden Lee

“Sylvia amazed me with her breadth of knowledge and enthusiasm for teaching. No matter what the subject—baroque, spiritual, you name it—Sylvia had been there, done that, and was willing to share with us. There are so many of us who consider ourselves Sylvia disciples. It is hard to imagine a world without her.” —Jessye Norman*

Sylvia Olden Lee’s remarkable life felt like a symphony of perseverance, passion, and pioneering firsts. A world-renowned pianist and vocal coach, the esteemed Curtis faculty member, who served at the school from 1970–90, shaped the voices of some of the most celebrated opera singers of the 20th century, including Osceola Davis (Opera ’72), Kathleen Battle, Jessye Norman, and Marian Anderson. Her influence stretched beyond mere technique—throughout her life, she instilled in her students a deep emotional connection to their craft, championed the inclusion of African American spirituals in the classical repertoire, and fearlessly broke racial barriers in the opera industry.

Born in Meridian, Mississippi, on June 29, 1917, Ms. Lee seemed destined for a life as a musician. Her mother, Sylvia Alice Ward, was a gifted soprano and pianist, and her father, James Olden, was a minister and a vocalist. By age five, she was learning the piano, and by eight, she was accompanying her parents during performances, a remarkable feat that foreshadowed the virtuosity and artistry she would later bring to stages and conservatories across the world.

Born in Meridian, Mississippi, on June 29, 1917, Ms. Lee seemed destined for a life as a musician. Her mother, Sylvia Alice Ward, was a gifted soprano and pianist, and her father, James Olden, was a minister and a vocalist. By age five, she was learning the piano, and by eight, she was accompanying her parents during performances, a remarkable feat that foreshadowed the virtuosity and artistry she would later bring to stages and conservatories across the world.

At ten, she was giving piano recitals outside her home, and at 16, she was invited to perform at the White House for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s inauguration in 1933. Later, in 1942, she was invited back by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for another performance, further cementing her musical presence among the nation’s cultural elite.

She first pursued her studies at Howard University but later transferred to the Oberlin Conservatory of Music on a full scholarship, where she thrived both academically and artistically, participating in the Musical Union and becoming a member of the Pi Kappa Lambda honor society. After graduation in 1938, she entered a world where opportunities for African American musicians were few and far between, but her determination to exceed all expectations and excel knew no bounds. It was during this period that she toured throughout the South with American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional football player, and activist Paul Robeson, using her music and highly visible performances as a platform to challenge racial injustice. She also began teaching at several institutions of higher learning, including Howard University, Oberlin College, Columbia University, and Dillard University in New Orleans.

She first pursued her studies at Howard University but later transferred to the Oberlin Conservatory of Music on a full scholarship, where she thrived both academically and artistically, participating in the Musical Union and becoming a member of the Pi Kappa Lambda honor society. After graduation in 1938, she entered a world where opportunities for African American musicians were few and far between, but her determination to exceed all expectations and excel knew no bounds. It was during this period that she toured throughout the South with American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional football player, and activist Paul Robeson, using her music and highly visible performances as a platform to challenge racial injustice. She also began teaching at several institutions of higher learning, including Howard University, Oberlin College, Columbia University, and Dillard University in New Orleans.

In 1952, she and her husband, violinist and conductor Everett Lee Jr., were both awarded Fulbright Scholarships to study in Italy. While there, she immersed herself in opera and oratorio at the prestigious Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome. A few years later, in 1956, they relocated to Germany, where she received a government grant to produce television specials introducing diverse audiences to classical music. During those seven years abroad, she and her husband continued to find work throughout Germany, but in 1963, as opportunities for Black conductors remained scarce in the U.S., the couple decided not to return, and he accepted a post in Norrköping, Sweden, as chief conductor of the town symphony. Ms. Lee went on to stage and produce full and concert versions of operas, including the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, and gave live radio and recorded performances, performing as a piano soloist in concerts with symphonies throughout Scandinavia. Their marriage ultimately ended in divorce during the early 1980s.

In 1952, she and her husband, violinist and conductor Everett Lee Jr., were both awarded Fulbright Scholarships to study in Italy. While there, she immersed herself in opera and oratorio at the prestigious Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome. A few years later, in 1956, they relocated to Germany, where she received a government grant to produce television specials introducing diverse audiences to classical music. During those seven years abroad, she and her husband continued to find work throughout Germany, but in 1963, as opportunities for Black conductors remained scarce in the U.S., the couple decided not to return, and he accepted a post in Norrköping, Sweden, as chief conductor of the town symphony. Ms. Lee went on to stage and produce full and concert versions of operas, including the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, and gave live radio and recorded performances, performing as a piano soloist in concerts with symphonies throughout Scandinavia. Their marriage ultimately ended in divorce during the early 1980s.

In 1954, she shattered racial barriers when she became the first African American musician employed by the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Serving as vocal coach at the largest repertory opera house in the world was nothing short of groundbreaking at the time, and Ms. Lee played an integral part in preparing contralto Marian Anderson for her historic 1955 performance as Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera. A watershed moment in American musical history, this performance marked the first time an African American had ever sung a principal role at the Met.

In 1954, she shattered racial barriers when she became the first African American musician employed by the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Serving as vocal coach at the largest repertory opera house in the world was nothing short of groundbreaking at the time, and Ms. Lee played an integral part in preparing contralto Marian Anderson for her historic 1955 performance as Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera. A watershed moment in American musical history, this performance marked the first time an African American had ever sung a principal role at the Met.

In 1970, the couple moved to the Germantown neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia to tackle a new role that would define the latter part of her career—vocal coach in the opera department at Curtis. Over the next two decades, she became a mentor to countless students, instilling in them not only technical acumen but also a deep, heartfelt appreciation for the emotional and cultural significance of the music each of them performed. A stalwart advocate for the inclusion of African American spirituals in the classical repertoire, Ms. Lee believed each student held a unique power to communicate the entire human experience in their artistry, and she urged her students to look beyond the notes on a manuscript page, teaching them to connect with the stories these songs, arias, and spirituals told. Ms. Lee continued to coach opera singers at the Met and conduct master classes worldwide until shortly before her death from pancreatic cancer on April 10, 2004, at age 86.

In 1970, the couple moved to the Germantown neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia to tackle a new role that would define the latter part of her career—vocal coach in the opera department at Curtis. Over the next two decades, she became a mentor to countless students, instilling in them not only technical acumen but also a deep, heartfelt appreciation for the emotional and cultural significance of the music each of them performed. A stalwart advocate for the inclusion of African American spirituals in the classical repertoire, Ms. Lee believed each student held a unique power to communicate the entire human experience in their artistry, and she urged her students to look beyond the notes on a manuscript page, teaching them to connect with the stories these songs, arias, and spirituals told. Ms. Lee continued to coach opera singers at the Met and conduct master classes worldwide until shortly before her death from pancreatic cancer on April 10, 2004, at age 86.

In 2017, a centennial celebration concert at Carnegie Hall, Sylvia Olden Lee: Through Beauty, to Freedom—March On!, honored her life’s work, featuring performances by artists she had mentored and inspired. More than a pianist or vocal coach, Ms. Lee was a trailblazing force of nature who championed the inclusion of Black musicians in classical music, and her legacy lives on through the artists she guided and the doors she kicked wide open for future generations of singers.

* Jessye Norman’s quote from Foundation for the Revival of Classical Culture