Celebrating Women's History: Q&A with Constance Fee (Opera '77)

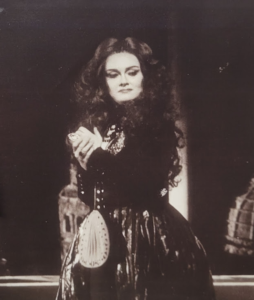

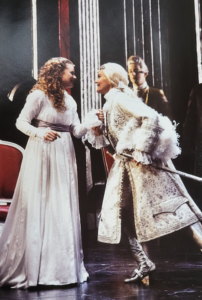

Hailed in Opernwelt Berlin as “vocally brilliant, dramatically spontaneous, and thoroughly alive,” internationally renowned opera singer, voice professor, and Curtis alumna Constance Fee (Opera ’77) has garnered acclaim for her  performances of over 50 soprano and mezzo-soprano roles. Throughout her career, she graced the stages of such prestigious houses as the Opéra de la Bastille, Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, Opéra de Lyon, Netherlands Opera, Staatsoper Stuttgart, l’Opéra Royal de Wallonie in Belgium, and Houston Grand Opera, and appeared as soloist with such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic and the Czech Philharmonic before joining the faculty of Roberts Wesleyan University as the director of vocal studies and associate professor of vocal performance in Rochester, New York. Ms. Fee has also taught voice and French diction on the faculty of the Franco-American Vocal Academy in Périgueux, France, and since 2014, has been a member of the voice faculty of the Crescendo Summer Institute in Tokaj, Hungary.

performances of over 50 soprano and mezzo-soprano roles. Throughout her career, she graced the stages of such prestigious houses as the Opéra de la Bastille, Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, Opéra de Lyon, Netherlands Opera, Staatsoper Stuttgart, l’Opéra Royal de Wallonie in Belgium, and Houston Grand Opera, and appeared as soloist with such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic and the Czech Philharmonic before joining the faculty of Roberts Wesleyan University as the director of vocal studies and associate professor of vocal performance in Rochester, New York. Ms. Fee has also taught voice and French diction on the faculty of the Franco-American Vocal Academy in Périgueux, France, and since 2014, has been a member of the voice faculty of the Crescendo Summer Institute in Tokaj, Hungary.

Born to an orthodontist father and classical vocalist mother who taught voice and played organ and piano, Ms. Fee began taking piano lessons at age four, discovered her love for singing at 15, and eventually followed in her mother’s footsteps to study at Westminster Choir College in Princeton, N.J., where she received her bachelor’s degree in music education. Touring with the famous choir and performing at Lincoln Center under the baton of such luminaries as Leonard Bernstein (Conducting ’41), Ms. Fee’s studies eventually led her to Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music for her master’s degree in vocal performance, and Curtis, studying with legendary teacher Margaret Harshaw.

What circumstances, whether in your formative years or as you continued your studies, led you to apply to Curtis?

When it came time to graduate from Westminster, I had a wonderful teacher who taught an opera course. After my student teaching in the fall of my senior year, he sat me down and asked, “Graduating in May, are we? What are you going to do?” I said, “I know one thing: I’m not teaching in public school. It’s not for me.” He laughed and said, “You know you have to sing, right?” I said, “Yes.”

When it came time to graduate from Westminster, I had a wonderful teacher who taught an opera course. After my student teaching in the fall of my senior year, he sat me down and asked, “Graduating in May, are we? What are you going to do?” I said, “I know one thing: I’m not teaching in public school. It’s not for me.” He laughed and said, “You know you have to sing, right?” I said, “Yes.”

For years, I would sit in the Westminster Symphonic Choir and look at the soloists working with the conductor up front. I’d watch them breathe, interact, and listen to their performances. I knew that was what I wanted to do. I asked him for advice on how I could get there, and he told me I needed to study with Margaret Harshaw, who he said was the best voice teacher in the country. She taught for many years at Indiana University and at Curtis from 1970 to ’77. She taught at both schools, so I auditioned at Curtis and also at AVA (as my backup). I was ridiculously naïve but had incredible exposure to high-level singing at Westminster. My voice teacher was Diane Curry, who sang at [New York] City Opera for many years.

My audition at Curtis was interesting. At Westminster, we had a small vocal group that did baroque music. The conductor of that group gave me a wonderful bravura aria by [Polish Baroque-era composer] Damian Stachowicz, with lots of runs and high notes. I learned it and used it for my audition at Curtis, along with a Mozart aria and some other pieces. I was singing mezzo at the time, and I had my four pieces but no opera experience. They were all there at the audition—Rudolf Serkin, Mme. Gregory, Max Rudolf, Dino Yiannopoulos, and Ms. Harshaw. At the time, I didn’t really understand what Curtis was: To me, it was just this music school in a house behind the Academy of Music, where Westminster Choir performed often. I just knew that I wanted to study with that teacher.

My audition at Curtis was interesting. At Westminster, we had a small vocal group that did baroque music. The conductor of that group gave me a wonderful bravura aria by [Polish Baroque-era composer] Damian Stachowicz, with lots of runs and high notes. I learned it and used it for my audition at Curtis, along with a Mozart aria and some other pieces. I was singing mezzo at the time, and I had my four pieces but no opera experience. They were all there at the audition—Rudolf Serkin, Mme. Gregory, Max Rudolf, Dino Yiannopoulos, and Ms. Harshaw. At the time, I didn’t really understand what Curtis was: To me, it was just this music school in a house behind the Academy of Music, where Westminster Choir performed often. I just knew that I wanted to study with that teacher.

I started with the baroque piece, and then they asked for “Must the Winter Come so Soon” [from Samuel Barber’s (Composition ’34) opera Vanessa]. The woman playing the audition was also on staff at the Music Academy of the West, so it’s not possible that she didn’t know the repertoire. As she started playing the Barber, I realized something was wrong and said to her out loud, “Oh no, that’s the wrong tempo!” I think they might have wanted to see how I would handle that. In the end, I did just fine. Anyway, I got into both schools, and when the assignments came, I was put in Charles Kullman’s studio. [Eventually, Ms. Fee switched studios to work with Margaret Harshaw, followed her to Indiana, and ultimately, back to Curtis].

I started with the baroque piece, and then they asked for “Must the Winter Come so Soon” [from Samuel Barber’s (Composition ’34) opera Vanessa]. The woman playing the audition was also on staff at the Music Academy of the West, so it’s not possible that she didn’t know the repertoire. As she started playing the Barber, I realized something was wrong and said to her out loud, “Oh no, that’s the wrong tempo!” I think they might have wanted to see how I would handle that. In the end, I did just fine. Anyway, I got into both schools, and when the assignments came, I was put in Charles Kullman’s studio. [Eventually, Ms. Fee switched studios to work with Margaret Harshaw, followed her to Indiana, and ultimately, back to Curtis].

I was there with Sharon Sweet, Carlos Serrano (Opera ’77), Michael Myers (Opera ’77), and Sally Wolf (Opera ’77), now teaching at AVA. I spent time at IU from ’73 to ’76, went to Marlboro for the summer, and then went back to Curtis for the opera program in the fall of 1976. Then, in the spring of my opera certificate year at Curtis, which was Harshaw’s last year, Curtis got a call from Plato Karayanis (Voice ’56) asking for a baritone and a mezzo to come to NYC to audition for the first year of the Merola program. [Ms. Fee auditioned alongside baritone Carlos Serrano for Mr. Karayanis but was recommended for the inaugural Houston Opera Studio with Houston Grand Opera].

I was there with Sharon Sweet, Carlos Serrano (Opera ’77), Michael Myers (Opera ’77), and Sally Wolf (Opera ’77), now teaching at AVA. I spent time at IU from ’73 to ’76, went to Marlboro for the summer, and then went back to Curtis for the opera program in the fall of 1976. Then, in the spring of my opera certificate year at Curtis, which was Harshaw’s last year, Curtis got a call from Plato Karayanis (Voice ’56) asking for a baritone and a mezzo to come to NYC to audition for the first year of the Merola program. [Ms. Fee auditioned alongside baritone Carlos Serrano for Mr. Karayanis but was recommended for the inaugural Houston Opera Studio with Houston Grand Opera].

I had already decided to go to Europe, visit my friends who had fest positions there, and do some auditions. But I thought, well if he’s gone to this trouble, I’ll go ahead and do the HGO audition. So I went back to New York, walked into the cattle call, and saw all the divas with the hair, dresses, and makeup milling around. I went in for my turn and saw the little table with the phone David Gockley had spoken on when I called him to arrange my audition time. There he was with Carlisle Floyd. I walked in, and sang my entire package: Composer’s Aria, Cenerentola, a French aria, and I was probably still using “Must the Winter Come so Soon” [from Samuel Barber’s Vanessa] for my English aria. As I came down the steps of the little stage, Carlisle Floyd took my elbow, walked me out into the lobby with all the other singers, and said, “You’re exactly what we’re looking for. Can you come to Houston at the end of August? This program is to replace the need for American singers to have to go to Europe to start their careers.”

I had already decided to go to Europe, visit my friends who had fest positions there, and do some auditions. But I thought, well if he’s gone to this trouble, I’ll go ahead and do the HGO audition. So I went back to New York, walked into the cattle call, and saw all the divas with the hair, dresses, and makeup milling around. I went in for my turn and saw the little table with the phone David Gockley had spoken on when I called him to arrange my audition time. There he was with Carlisle Floyd. I walked in, and sang my entire package: Composer’s Aria, Cenerentola, a French aria, and I was probably still using “Must the Winter Come so Soon” [from Samuel Barber’s Vanessa] for my English aria. As I came down the steps of the little stage, Carlisle Floyd took my elbow, walked me out into the lobby with all the other singers, and said, “You’re exactly what we’re looking for. Can you come to Houston at the end of August? This program is to replace the need for American singers to have to go to Europe to start their careers.”

I wouldn’t have learned how to sing or had the life I now enjoy if it hadn’t been for Curtis. It was absolutely life-changing for me.

What were some of your fondest memories of attending Curtis, and are there any specific moments or performances that stand out as most memorable?

There were often performances in II-J, including Rigoletto and Pelléas et Mélisande. We did some big productions there with piano; we also performed at the Walnut Street Theatre, where I did a Così [fan tutte] with Julia Conwell (Opera ’77) as my Fiordiligi. I remember a wonderful performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream there. My nickname was “Hermia-on-the-Ground” because of one of the lines in the text. Gwendolyn Bradley (Opera ’77) was singing Tytania. Someone in the cast wore a long train in that production, and there I am, on the ground; they walk over me, and the train with all the dust and dirt is dragged over my head while I’m lying there. [Laughs] After Curtis, my life took a completely different direction than I had ever anticipated. Now, I’m in my second career and I’ve been teaching longer than my 20-year performing career.

There were often performances in II-J, including Rigoletto and Pelléas et Mélisande. We did some big productions there with piano; we also performed at the Walnut Street Theatre, where I did a Così [fan tutte] with Julia Conwell (Opera ’77) as my Fiordiligi. I remember a wonderful performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream there. My nickname was “Hermia-on-the-Ground” because of one of the lines in the text. Gwendolyn Bradley (Opera ’77) was singing Tytania. Someone in the cast wore a long train in that production, and there I am, on the ground; they walk over me, and the train with all the dust and dirt is dragged over my head while I’m lying there. [Laughs] After Curtis, my life took a completely different direction than I had ever anticipated. Now, I’m in my second career and I’ve been teaching longer than my 20-year performing career.

What was it like studying with Margaret Harshaw, who taught at Curtis during the 1970s?

Miss Harshaw started her Met career as a mezzo and then switched to soprano. As I understand it, she still holds the record for performing the most Wagner roles there because she sang all the mezzo roles and then all the soprano roles. She had years of experience and knew what she was doing. She had incredible training and was a remarkable teacher.

Miss Harshaw started her Met career as a mezzo and then switched to soprano. As I understand it, she still holds the record for performing the most Wagner roles there because she sang all the mezzo roles and then all the soprano roles. She had years of experience and knew what she was doing. She had incredible training and was a remarkable teacher.

Harshaw studied with a woman named Anna E. Schoen-René at Juilliard, and Schoen-René had studied with Pauline Viardot-García and her brother Manuel García, so her work with them was just two generations ago. The Garcias lived until they were 89 and 101 years old—probably because of their deep breathing! At first, she was very nurturing and encouraging and, you know, carefully, slowly, tediously, over and over, getting things built in from the ground up. I had a natural technique, but I had no clue how to develop it and make it consistent.

Miss Harshaw lined everything up and gave me access to skills without my even realizing it. It was just because of the work she did, the exercises she gave me, and the way she described things with images and sounds. She had a way of really getting you in touch with your natural instincts. When you did something that touched her artistically, her eyes would brim with tears, and she would look at you and say, “I wish I could give you everything I know right now.” She was very demanding, and when you didn’t do something she knew you were capable of, another side of her personality would appear, her eyes would flare, and I would hear her say, at the top of her voice, “Well, Schoen-René only had to say it ONCE!”

Then there were her stories. I would listen to stories for hours, learning about the profession. When an interviewer once asked her the most important qualities a singer must have to become a successful artist, she said, “Integrity, integrity, and integrity.” Now, I try to guide my students to their own natural instincts. I tell them that I can’t teach them how to sing, but I can show them that they already know how. As a singer, it’s probably never going to sound good to you in your own head. You may not like how you think it sounds, but you’re going to love how it feels.

Then there were her stories. I would listen to stories for hours, learning about the profession. When an interviewer once asked her the most important qualities a singer must have to become a successful artist, she said, “Integrity, integrity, and integrity.” Now, I try to guide my students to their own natural instincts. I tell them that I can’t teach them how to sing, but I can show them that they already know how. As a singer, it’s probably never going to sound good to you in your own head. You may not like how you think it sounds, but you’re going to love how it feels.

What advice do you have for current Curtis vocal students and recent alumni?

Focus on your gift and on developing it to its fullest potential. Get the help you need. Speak up. Be your own advocate. Don’t just do what you see other people do. Do what’s right for you. There’s no written pathway now. When I was at Curtis and IU, there was a path you could follow that was already laid out: You went to Europe, sang for the agents, got a fest job in an opera house, and gained your street creds there. Now, you can make videos, put them up on Instagram, and start your career here. There’s no clear, defined pathway now. You can make your own pathway, but always be true to yourself. Don’t let other people take advantage of your talent, and don’t use it to get somewhere. Use it to say something. Whoever you are, you are unique, and you owe it to the world to discover your gifts and develop your art.

Focus on your gift and on developing it to its fullest potential. Get the help you need. Speak up. Be your own advocate. Don’t just do what you see other people do. Do what’s right for you. There’s no written pathway now. When I was at Curtis and IU, there was a path you could follow that was already laid out: You went to Europe, sang for the agents, got a fest job in an opera house, and gained your street creds there. Now, you can make videos, put them up on Instagram, and start your career here. There’s no clear, defined pathway now. You can make your own pathway, but always be true to yourself. Don’t let other people take advantage of your talent, and don’t use it to get somewhere. Use it to say something. Whoever you are, you are unique, and you owe it to the world to discover your gifts and develop your art.

Interview with Constance Fee by Ryan Scott Lathan.

Please visit the Curtis Institute of Music Open Archives and Recitals (CIMOAR). Learn more about Curtis’s library and archives HERE.

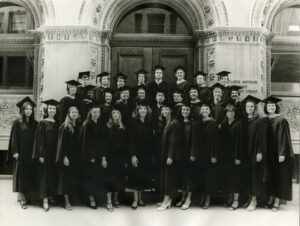

All photos courtesy of Constance Fee. Top banner image by Christian Steiner and photo 8 by Lisa Kohler. Photo 3 of Ms. Fee as Giulietta in Les contes d’Hoffmann from Vienna Volksoper. Photo 5 is Curtis’s graduating class of 1977, courtesy of the Curtis Archives; Ms. Fee is in the first row on the right. Images of Ms. Fee performing the title roles in Carmen (6, 9, 12) and La Cenerentola (4, 7, 11) all taken from productions at Stadttheater Luzern. Photo 10 of Ms. Fee as Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier at Welsh National Opera.